The Politics of Victimhood in Conflict Resolution

The Politics of Victimhood in Conflict Resolution

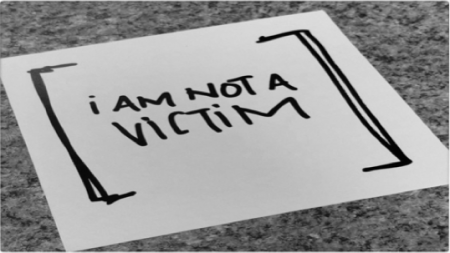

On November 6, 2015, Dr. Sara Cobb and the Center for Narrative and Conflict Resolution hosted a conference on “The Politics of Victimhood in Conflict Resolution.” The event served as a space for scholars and practitioners to raise important questions regarding how we think about and categorize victims and perpetrators within a conflict context. The keynote speech was delivered by Diane Enns, with John Winslade as the discussant. Conference presentations were organized into five panels, each panel raising a different set of critical questions about the binary classification of victims and perpetrators. Each panel was followed by a facilitated discussion that engaged both presenters and the general audience in reflecting on the important questions and considerations that had been raised.

On November 6, 2015, Dr. Sara Cobb and the Center for Narrative and Conflict Resolution hosted a conference on “The Politics of Victimhood in Conflict Resolution.” The event served as a space for scholars and practitioners to raise important questions regarding how we think about and categorize victims and perpetrators within a conflict context. The keynote speech was delivered by Diane Enns, with John Winslade as the discussant. Conference presentations were organized into five panels, each panel raising a different set of critical questions about the binary classification of victims and perpetrators. Each panel was followed by a facilitated discussion that engaged both presenters and the general audience in reflecting on the important questions and considerations that had been raised.

The first panel was on “Challenging categories.” Presentations by Sarah Federman, Claudine Kuradusenge, Chitra Nagarajan, and Margarida Hourmat addressed the power that can accompany victimhood and the victim’s ability to silence and marginalize others. They directed the audience to consider the importance of both challenging and destabilizing the categories that challenge narrative legitimacy. The discussant, Dr. Solon Simmons, raised important questions about the role of the victim-perpetrator binary in conflict resolution. When is this binary categorization necessary, for instance for the production of solidarity, and when does it limit our ability to move forward and recognize the gray areas between, and outside of, these categories?

Panel 2 focused on the stability and instability of victimhood, and included presentations by Tony Walsh, Samantha Borders, Ramzi Kysia, and Karina Korostelina, who encouraged the audience to think about the implications of victimhood as an identity. How is an individual positioned in society when he or she is labeled as a victim? How does victimhood affect an individual’s agency? Dr. Nathanial Greenberg drew from these questions that were raised to discuss both the possibilities and limitations that are present in victim narratives, and in considering how we, as practitioners, can work with these narratives in the process of conflict transformation.

Joshua Stephani, Roxanne Krystalli, and Alison Castel presented the third panel on Colombia as a case study for applying some of the critical questions that had been raised surrounding the notion of victimhood. More specifically, speakers discussed the the ways that victim-perpetrator dynamics determine who can and cannot speak out, and focused on the implications of victimhood within the context of the ongoing conflict and peace process in Colombia. Jenny White led the follow-up discussion to consider the role of these binary categories in silencing certain storylines. Which stories are being legitimized, and who is working to resist the dominant narratives? Additionally, how is this narrative work affecting the quality of the peace process and, more specifically, what is the role of ascribed victims in shaping the process?

Joshua Stephani, Roxanne Krystalli, and Alison Castel presented the third panel on Colombia as a case study for applying some of the critical questions that had been raised surrounding the notion of victimhood. More specifically, speakers discussed the the ways that victim-perpetrator dynamics determine who can and cannot speak out, and focused on the implications of victimhood within the context of the ongoing conflict and peace process in Colombia. Jenny White led the follow-up discussion to consider the role of these binary categories in silencing certain storylines. Which stories are being legitimized, and who is working to resist the dominant narratives? Additionally, how is this narrative work affecting the quality of the peace process and, more specifically, what is the role of ascribed victims in shaping the process?

Following the third panel, keynote speaker Diane Enns focused on victim discourse as it applies to feminism, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and child soldiers. She discussed the complexity of conflict and the way in which the moral clout that comes with victimhood can make it difficult for us to recognize any overlap between victims and perpetrators. How can we acknowledge and respond to the experience of the victim in a way that doesn’t solidify their identity as such? Enns’ closing argument was formulated around the notion of “survival justice” as a form of political power that comes from people— both victims and perpetrators— acting together to make being about change. John Winslade engaged the audience in discussing the idea of how we might escape the victim-perpetrator binary while still managing to acknowledge and attend to victims.

The panels resumed with the fourth group of presenters, who focused on victimhood from a gender-based perspective. Speakers Jessica Smith and Lisa McLean, discussed how gender affects one’s ability to voice narratives of violence in different spaces, and how the binary categories of victim and perpetrator oversimplify the complexity that is present in these experiences of violence. Discussant RJ Nickels suggested the importance of narrative praxis in destabilizing dominant narratives and supporting strong counternarratives, and our duty as practitioners to create a discursive space that allows people to assume roles other than that of the victim.

The final panel was focused on complicating voices. Mollie Pepper, Pamina Firchow, Carlos Sluzki, Sara Ochs, and Kristin Reed gave presentations to support the argument for making victimhood more complex and acknowledging the role of narratives in driving conflict. Their ideas focused on “victim” storylines and destabilizing the rigid categories of victims and perpetrators. The discussant, Derek Sweetman, called upon the audience to consider whether we might need a space for anger and, if so, how much or little it should be contained.

The overarching themes that emerged from the conference focused on several key questions to consider when doing narrative work within a conflict context. How are our thoughts and actions constrained by the simplified binary categories that distinguish victims from perpetrators? Who can be a victim and who cannot? These are important questions to consider if we, as practitioners, want to challenge the rigidity of these categories and work to make conflict storylines more complex.