The Rwandan Genocide 22 Years Later

The Rwandan Genocide 22 Years Later

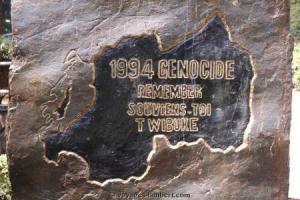

This year marked the 22nd commemoration of the Rwandan genocide that claimed over one million lives. Each year since 1994, Kwibuka, meaning “remember,” is held to commemorate the lives lost during the genocide. To encourage a commitment to oppose genocidal ideology, this year’s commemoration was held around the world under the theme Kwibuka 22: Fighting Genocide Ideology.

This year marked the 22nd commemoration of the Rwandan genocide that claimed over one million lives. Each year since 1994, Kwibuka, meaning “remember,” is held to commemorate the lives lost during the genocide. To encourage a commitment to oppose genocidal ideology, this year’s commemoration was held around the world under the theme Kwibuka 22: Fighting Genocide Ideology.

As a community, S-CAR had an opportunity to remember the Rwandan genocide at an event held on April 7, 2016. The first part of the evening was dedicated to watching a documentary titled Ubumuntu which translates to mean “humanness.” The plot of this movie followed Hutu families and a missionary priest who narrate why they decided to hide and save Tutsis, even at the risk of their own lives. This documentary reminded me of another situation, where students in Nyange in northern Rwanda, refused to obey the orders of killers to allow for the killing of Tutsis. These martyred students refused on the grounds that they were “all Rwandans.” Unfortunately their stance was shortlived as the militia attacked and killed many of them. These students still remain an inspiration for me and have even been honored as national heroes in Rwanda. They embody the vision that Rwandans desire and deserve, which is to live and die as Rwandan, and not as an exclusive ethnic group.

The Nyange students, the subject of Ubumuntu among many other living and dead Rwandans, protected each other with great love, radical care, compassion, mercy, patience, and courage. It is my hope that none of us at S-CAR have to make such a sacrifice, but if such an unfortunate situation presents itself as we engage in conflict resolution, management, and transformation work around the world, it is my belief that many of these courageous individuals from Rwanda can inspire us to say no to hatred and the culture of immoral or amoral indifference, and stand by those beleifs.

The second part of S-CAR's evening of commemoration involved a panel discussion which was uncomfortable, during certain periods. yet very important. The panel featured Dean Kevin Avruch; Rwandan Ambassador, Prof. Mathilde Mukantabana; Dr. Douglas Irvin-Erickson, Director of the Genocide Prevention Program at Mason; Dr. Zachary D. Kaufman, a fellow at both Harvard and Yale Universities; and myself, who served as the moderator. These distinguished scholars helped the audience discuss the 1994 genocide in light of the past, present, and the future of Rwanda. I extend thanks to all who were able to attend and special thanks to the panelists, who reminded us that our words and our actions or inaction have costs and consequences in the context of genocide. The way we educate our children at school and within the family, construct our history and memory, exercise national and international justice, lead and exercise power nationally and internationally, and finally the way we worship and practice religion all matter in promoting or preventing genocide and genocide ideology.

In the past 22 years and in the process of preparing for Kwibuka 22, I have had opportunities to interact with friends, colleagues, fellow Rwandans, and non-Rwandans who either challenge or support “the truth” about remembering the genocide. The major categories that I have encountered are those who believe that surviving the genocide is a privilege and so remembering is a duty; those who believe that remembering the genocide is a must, lest we forget and see a recurrence, as “Genocide Never Again” meaning nothing in Rwanda and many other places around the globe.

In addition, we also have those who believe that remembering prevents genocide victims from forgiving, forgetting, and reconciling; those who believe that remembering is not in the interest of the victims but of politicians, both governmental and opposition, who use commemoration to score political points; and finally those who deny that a Tutsi Genocide took place and believe that it was simply people killing people, with both Tutsis and Hutus killing equally, and as such Tutsis should not monopolize it.

The above positions and conflicts remind me how complex the word “truth” is. No wonder Immanuel Kant had to write three volumes about this concept. Both synthetic and analytic judgments are based on truth, which presupposes fact, reality, and authenticity. Mindful of such complexity of “truth,” I believe that we should not politicize an event such as the April 1994 Tutsi genocide. I hope to continue the conversation with myself, our panelists, and others about the 1994 genocide. Maybe S-CAR, as an academic institution for conflict analysis and resolution, and as the home of faculty such as Dr. Erickson, Director of the Genocide Prevention Program at Mason, and Dr. Stanton Gregory of Genocide Watch, can consider starting a memory center about this genocide, which can help to address and resolve conflicts that have continued for 22 years.

As a member of civil society, witnessing the genocide and its aftermath, losing so many family members and fellow Rwandans, and seeing so many people left traumatized, I have come to believe that a culture of remembering and honoring the memory of the genocide is inextricably linked with a culture of gratitude, hope, and healing. Hence, a culture of “remembering” in “truth” remains important for the future of Rwanda.

### Photo: Rwanda and Ouganda: An exceptional journey for lovers of Africa! by Flickr User Voyages Lambert.