Book Review - Work: Capitalism. Economics. Resistance.

Ph.D Conflict Analysis and Resolution, George Mason University

|

For those new to contemporary, post-Seattle/WTO anarchism, CrimethInc. may not be a term all too familiar. For the rest of us, these folks are seen as a prominent voice in the modern radical milieu, publishing a series of widely ready books, pamphlets, magazines, films, websites, etc. CrimethInc.manages to mix lifestyleist politics with highbrow theory, and wrap it all in a well designed package of allure and militancy, masked with a bit of clandestine conspiring. Call them escapist provocateurs or the modern day Situationists, they are a force to be reckoned with.

CrimethInc.’s 2011 book, Work: Capitalism. Economics. Resistance., is an analytically rich text designed to diagram late capitalism within a critical context, exposing the hierarchical relationships that produce structural oppression, while alerting the reader to strategies to not only create ruptures for one’s emancipation, but also provide insight as to the formation of a movement-level push against capitalism’s advancement. Like all of CrimethInc.’s books, the authors’ identities are concealed within a mysterious collective moniker, this infamous “CrimethInc. Ex-Workers’ Collective.” Work’s anonymous authors are keen to acknowledge that they themselves are not scholars, economists, philosophers or ‘experts,’ but that the analysis of capitalism is a task anyone can interact with. In their introduction, the authors write:

“This project is the combined effort of a group of people who have already spent many years in pitched struggle against capitalism. What qualifies us to write this?…all of us have lived under capitalism since we were born, and that males us experts on it. The same goes for you. No one has to have a degree in economics to understand what’s happening: it’s enough to get a paycheck or a pink slip andpay attention.” (2011, p. 7)

This style of non-expert, expert analysis permeates the entire book and serves to make the text accessible, informed, and extremely approachable. The examples are drawn from ‘average’ human experiences infused with the generalized anti-capitalist critique. In a sense, the book says, ‘Even if you don’t know what capitalism or wage slavery is, you know oppression because you know the frustration, alienation and drudgery of work.’ In this manner, CrimethInc. asserts that every individual is a philosopher, every worker a economist, and every annoyed consumer an insurgent.

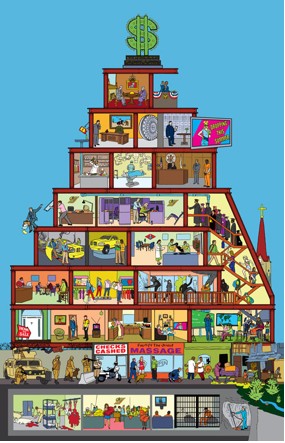

The book is broken down into four main areas. First, the authors provide a broad stroke exposé of the structure of capitalism, wage labor, the changing nature of the economy, and the structuring of the physical environment as it pertains to communities. Following this introduction, the book shifts structural gears and begins the “Positions: Where We Are” portion which examines the hierarchy of employment fields from the owning and political classes at the top of the pyramid, all the way down to the natural resources exploited for production at its base. In this section, the authors explore nineteen areas including “bosses,” “middle management,” “self-employment,” “factory workers,” “students,” “the service industry,” domestic labor,” “police and military,” “migrant labor,” “prisoners,” “unemployment and homelessness” as well a those that fall outside of the formal economy. Each of these fields is addressed in a mini vignette where their social, economic, and political (or lack there of) relationships are examined in terms of power, control, and avenues of exploitation. The hierarchical ranking of these fields provides a contextual framework for the furtherance of CrimethInc.’s larger thesis, namely, the diagramming of late capitalism via a pyramid structure with owners and politicians at the top, and migrant labor and prison labor at the bottom. They lead the reader towards their tagline summation, displayed prominently on the book’s accompanying poster, which reads: “capitalism is a pyramid scheme.”

Following the industry-by-industry breakdown, the authors shift their analysis to the “mechanics” of capital accumulation, examining the role played by a host of social institutions including the media, banking, taxes, inheritance, religion and gentrification. Sprinkled throughout these mechanistic explorations are discussions of manners of resistance such as “vertical alliances,” “illegal capitalism,” “theft,” and “subculture.” It is through these small windows of utopianism that the authors lead towards the fourth and final section entitled “The Resistance.” Predictably, in this section, the authors not only provide suggestions for the formulation of a mass opposition, but also critique piecemeal and reformist measures typically offered by social movements. The “Resistance” section begins with the heading, “We Don’t Have to Live Like This,” and offers exciting avenues of conjecture with accompanying images of riots, destroyed property, and subcultural counter institutions and artifacts such as squatted buildings and ant-capitalist street art.

The nature of the economic, social, and political critique offered by CrimethInc. is nebulous and sometimes difficult to succinctly pin down. On the one hand, the analysis is a classical Marxist structural critique, heavily influenced by the post-anarchist tendencies of the French Situationists, eco-primitivists, anti-Statist communists, and insurrectionary theorists. In a broad survey, the authors break the system of capitalism into three distinct classes, then capitalists, the exploited, and the excluded. Here, the capitalists are those directing the manner in which capital is created, owned and managed, while the exploited include all manners of laborers—from office workers and students to service workers and educators—that do not control either the products of their labor nor the methods of production. The capitalists “profit from others’ labor” (2011, p. 42), while the exploited’s “activity turns a profit for others.” (ibid.) In this pyramid diagram seen throughout the book, this exploited class is the largest unit and constitutes most of Marx’s category of proletariat.

What CrimethInc. adds uniquely, is a third category beyond bourgeoisie and proletariat: the excluded. In their description of the excluded, the authors write that members of this class “are left out of the equation and have to survive on the fringes of the economy.” (ibid.) While a traditional Marxist analysis would lump the excluded within the category of the exploited (proletariat), CrimethInc.’s model differentiates these workers through their lack of interaction in even the regulated economy of wage slavery. Included in this category are sex workers, soldiers, those who make money from illegal theft and drug sales, and those waged workers existing at the very bottom of the hierarchy, such as ‘undocumented’ workers and those whom are incarcerated and labor within the prison system.

In examining the uniqueness of CrimethInc.’s addition to the classical Marxist narrative, we can explore their treatment of “the sex industry” as a category of exploited proletariat labor. In this chapter, CrimethInc. draws from post-modern feminist theory by arguing that prostitutes and other sex workers are “demanding payment up front for things everyone else sells in a roundabout fashion.” (2011, p. 123) In this manner, CrimethInc. begins their positioning of sex work as simply another industry of production, one in which the commodity being traded is service work, the service of sex. Contained within this discussion is a nuanced examination of the flow of sex work profits beyond the individual street workers, and upwards towards the sexualized sale of Hollywood products, commercial pornography, and other manners in which sexual production is commodified and sold. In their latter analysis, the authors pay tribute to intersectional theory (e.g. Judith Butler, Anne Fausto-Sterling) and discuss how the sale of sex interacts with gender construction and the physical sexing of the body. In their treatment of the sex industry, CrimethInc. pushes the argument that this exploited worker is not unique, but rather yet another waged employee within an unregulated economy. In this logic, the exceptionalism of prostitution and pornography is removed in an attempt to show the uniformity of exploitation, alienation, and abstraction found in all waged labor from those who produce car batteries to those that produce orgasms.

In establishing the limitations and pitfalls of Work, one can point to the opacity of its representation of the intellectual traditions from which it draws from, as well as the hidden constitution of its authorship. The CrimethInc. writing style is one of cryptic references and subcultural innuendo drawn from its roots in the late 1990s hardcore punk and anarchist scenes. Following CrimethInc.’s rise to visibility that proceeded the 1999 World Trade Organization riots in Seattle, the network’s publications have taken on a certain mythical character amongst the contemporary anti-authoritarian left. Beginning with their introductory book-length work, Days of War, Nights of Love published in 2000, the anonymous authors of these insurrectionary texts have been careful to pen revolutionary prose while removing references to the intellectual forbearers. For the anonymous CrimethInc.ers, such intellectual antecedents can often be understood as mired within the ideology of philosophy and the products of dead, irrelevant, old and stagnant theoreticians.

While CrimethInc.’s obfuscation of these foundational authors is an intentional practice that creates a very readable text, for those seeking to read backwards, and to trace the roots and journeys such ideas took, the book leaves a great deal absent. The absence of such citations is so glaring, that in an unusual head nod to their unorthodoxy the authors include a “bibliography” where they write:

“We’ve chosen to forego formal citations for this project; in the Google era, it should be easy enough to follow up on any of our claims. This opens a host of questions that usually go unacknowledged in texts about economics. How do certain forms of corroboration benefit from and reinforce academic legitimacy, itself a currency of power?…Who benefits from this, and whom does it silence. We’ve drawn on more sources than we could enumerate, but here are a few good starting points.” (2011, p. 372)

In pointing the reader towards their ‘sources,’ CrimethInc. avoids citing the traditional characters and instead directs the reader towards Guy Debord the French Situationist, Silvia Federici the autonomous feminist, Eduardo Galeano the Uruguayan journalist and historian, Upton Sinclair the infamous muckraker, and even Prole.info a class struggle, anarcho-Marxist website. Excluded from this list are the typical leftist classical economic critics one would expect such as Marx, Engels, Lenin, Luxemburg, or contemporary anti-capitalist economists such as Michael Albert, Robin Hahnel, Noam Chomsky and others. In penning this bibliographic aside, the authors acknowledge their ‘unacademic’ and ‘unverifiable’ approach, and cite its basis in a rejectionism of the academic discipline’s reliance on measures of legitimacy. In this sense, the choice to present an intellectually rich argument devoid of intellectual markers can ether be seen as a destabilizing attempt to challenging traditional scholarship, or an attempt to pass off centuries of criticism as neo-anarchist propaganda. The decision on which goal is the authors’ intention is left up to the reader.

To cite a single (glaringly) obvious example of this tendency, the book is designed to function in tandem with an accompanying poster visually displaying the book’s thesis via a hierarchical pyramid of workers-atop-workers.

CrimethInc. “Work Pyramid”

IWW’s “Pyramid of Capitalist System”

While the authors’ acknowledge that their poster is a reinterpretation of a piece of 1911 propaganda produced by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) under the title “Pyramid of Capitalist System”, CrimethInc. shares this linkage without identifying the economic theories that inform it—in other words devoid of the more fundamental base/superstructure, bourgeoisie/proletariat, capital owner/worker taxonomies. While the visual adaptation is apparent in the book’s display of the IWW poster (on page 44), the book is noticeably without an examination of the surrounding theories. The effect of this writing style is the following: a reader is exposed to the concepts of alienation, commodity fetishism, worker-boss hierarchy, exploitation and the eventuality of revolutionary structural change, but they are denied a roadmap which traces such ideas back to their source texts. CrimethInc. accomplishes this task with brash honesty and pride in this style of intellectual anti-copyright. By not attributing the ideas to Marx, Luxemburg and others, the authors encourage a new generation of revolutionary readers to consider what is presented as fresh ideas. This serves to reinvigorate the discourse and not simply present it as yet another attempt to explain a revolutionary agenda that has failed to produce revolution. In this sense, CrimethInc. succeeds in ‘selling’ the ideas as novel, but in another sense it fails the reader in concealing a century and a half of intellectual struggle and debate.

This material is presented as the original analysis of analysts at S-CAR and is distributed without profit and for educational purposes. Attribution to the copyright holder is provided whenever available as is a link to the original source. Reproduction of copyrighted material is subject to the requirements of the copyright owner. Visit the original source of this material to determine restrictions before reproducing it. To request the alteration or removal of this material please email [email protected].