Rituals of Gendered Violence: School Girl Kidnappings in Nigeria

Ph.D., Conflict Analysis and Resolution 2007, George Mason University

M.S., Conflict Analysis and Resolution 2002, George Mason University

|

|

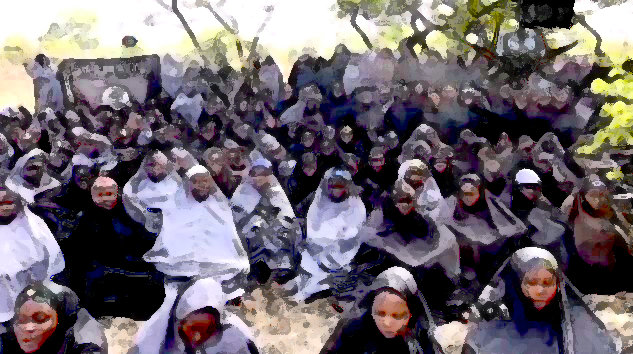

The recent kidnapping of almost 300 girls from their boarding school in the area of Chibok, Borno State, in northeastern Nigeria has elicited international outrage. The status of the girls and the approaches to finding and returning them to their families remain unclear and often contradictory. The kidnapping can be considered a political ritual: a public demonstration that influences people at civic and individual levels. In some cases, political rituals serve to unite individuals around a shared value or understanding. But rituals can also mobilize groups to action or create a climate of fear as a step toward conquest. Contextualizing the Nigeria kidnapping as one of many political rituals that occur during insurgency and civil war allows for case comparisons that can lead to a more nuanced exploration of potential outcomes, in particular concerning the girls, their families, and their communities.

Kidnapping has a long history in Nigeria as a countermeasure against staggering amounts of elite corruption, poor governance, security service brutality, political dissatisfaction, and lack of opportunities, particularly for youth. The Global Database of Events, Languages, and Tone (GDELT) tracks 25,247 kidnappings that occurred in Nigeria since 1982 (Nigeria Kidnapping Trends). In April 2014, the Chibok substate area of Borno saw 649 kidnappings with only one such event in 2013 and none previous to that date. Boko Haram makes that area its home base, which may account for a large percentage of that region’s kidnappings, but does not account for the pervasiveness of kidnapping across Nigeria as a whole. Given the poor state governance over most of the country and the historical prevalence of the practice, kidnapping – particularly of foreign nationals for ransom – makes sense as a resource-generating activity, one that happens in countries on almost every continent.

Kidnapping has a long history in Nigeria as a countermeasure against staggering amounts of elite corruption, poor governance, security service brutality, political dissatisfaction, and lack of opportunities, particularly for youth. The Global Database of Events, Languages, and Tone (GDELT) tracks 25,247 kidnappings that occurred in Nigeria since 1982 (Nigeria Kidnapping Trends). In April 2014, the Chibok substate area of Borno saw 649 kidnappings with only one such event in 2013 and none previous to that date. Boko Haram makes that area its home base, which may account for a large percentage of that region’s kidnappings, but does not account for the pervasiveness of kidnapping across Nigeria as a whole. Given the poor state governance over most of the country and the historical prevalence of the practice, kidnapping – particularly of foreign nationals for ransom – makes sense as a resource-generating activity, one that happens in countries on almost every continent.

Taking close to 300 girls away from school and into the Sambisa forest with almost no chance of a monetary reward from parents or government, on the other hand, does not fit in with the traditional model. The kidnappers might have planned to trade their hostages for group members held by the security services and made such a demand, which has, as of this writing, been denied.

Much attention has been paid to the ideological aspects of the organization and their possible links with terrorist groups. One of the foundational tenets of the Boko Haram organization is the rejection of all Western-influenced education, and the removal of the girls from such a school can be seen as part of this ideology. On the other hand, analyzing this large-scale kidnapping as an indicator of the disorder of a larger system requires a more inclusive exploration of the dense weave of ideology, politics, economics, power, regional dynamics, history, and gender construction. To explore the kidnapping as a political ritual meant to serve as an expression of power over, a vehicle for structural change, and a means to motivate both action and fear, allows a broader understanding of the kidnapping in light of the multiple dimensions of marginality young Nigerian women and men face on their transition to adulthood.

The girls were the targets of a political ritual with a distinct gendered violence aspect. Although there has been a large international push to increase the number of girls attending school, in many places where parents have little money boys are more often sent to school than girls. In many ways, the choice is an investment in the future; boys remain in the family even after marriage while girls traditionally join their husband’s family group. Boys continue to help support their natal family group but girls potentially need to be dowered, and after marriage contribute to their husband’s extended family. Targeting a girl’s school also targets the families who sent their daughters to get an education, families who themselves stepped outside the strict sanctions to keep girls at home, constrained to certain functions, and controlled by male family members.

The ritual act of large scale kidnapping also makes clear the inability of government at all levels to stop such political and social action and serves to paint the government as obviously weak and in many ways impotent – both domestically and internationally. Seen from these vantage points, the Boko Haram organization gains significantly. From a practical point of view they now control almost 300 girls to either take as wives or to sell and barter to other groups. Symbolically, they certainly upped the status of their reputation as a viable insurgent group, one that would be investment-worthy to other like-minded individuals.

The girls, on the other hand, encounter only further marginalization and suffering. In civil wars across the world girls involved with fighting forces prove very useful as spies, saboteurs, active fighters, wives, cooks, and so on. The probability that the Nigerian girls will engage in such activities seems high. The girls themselves will use their agency to survive the best they can while waiting for the experience to end.

Yet in countries such as Sierra Leone, Liberia, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo returning girls find that although they had little choice in whether or not to be part of these activities, community members can often struggle with accepting them back. Some families will welcome the girls home gratefully, others will hesitate, some will refuse to allow them to return. The girls could be seen as no longer innocent due to their experiences. There may be worries that they have been influenced by the ideology of the insurgent group rather than that of the family or community. They are perceived as constituting a danger to the family and community socio-cultural norms, values, and practices.

In country cases in Africa, as well as Sri Lanka and Colombia, where both boys and girls are kidnapped or pressed into insurgent group activities, the girls fare far worse when seeking to return to their communities. This underscores kidnapping as a ritual of gendered violence. Girls are seen to have engaged in unsanctioned sexual activities (an assumption with a high probability of truth) even if that sexual activity was within a forced marriage. In this way the girls experience violence twice, at the hand of the men involved and in the minds and subsequent actions of community members. Marriage could well prove impossible for them as a result, an outcome that would lead to a continuation of life outside the socially sanctioned existence for women, and thus further marginalization. If they return with children, those children will also experience the effects of the gendered violence of kidnapping throughout their own lives. The long shadow of corruption, violence, and other forms of gendered power that led to the kidnappings will continue to affect the lives of the victims.

###

Patricia Maulden is Associate Professor of Conflict Resolution at George Mason University and member of the Human Rights & Global Justice Working Group at the Center for Global Studies

This material is presented as the original analysis of analysts at S-CAR and is distributed without profit and for educational purposes. Attribution to the copyright holder is provided whenever available as is a link to the original source. Reproduction of copyrighted material is subject to the requirements of the copyright owner. Visit the original source of this material to determine restrictions before reproducing it. To request the alteration or removal of this material please email [email protected].

rosters

IMPORTANT LINKS

- Home

- Admissions

- Academics

- Research & Practice

- Center for Peacemaking Practice

- Center for the Study of Gender and Conflict

- Center for the Study of Narrative and Conflict Resolution

- Center for World Religions, Diplomacy, and Conflict Resolution

- Indonesia - U.S. Youth Leadership Program

- Dialogue and Difference

- Insight Conflict Resolution Program

- Parents of the Field Project

- Program on History, Memory, and Conflict

- Project on Contentious Politics

- Sudan Task Group

- Undergraduate Experiential Learning Project

- Zones of Peace Survey

- News & Events

- Student and Career Services

- Alumni

- Giving