What Aziz Abu Sarah learned in Hebrew school

|

Aziz Abu Sarah spent much of his early adulthood forcing himself to look at other sides of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

As a bereaved brother, whose older sibling died after a year-long imprisonment in an Israeli jail, his own journey from stone-throwing youth and Fatah organizer to conflict resolution worker and alternative tour organizer is about as drastic a transformation as one can find in the Middle East.

“If you go to places where you don’t agree with what they’re saying, it forces you to see other sides,” said peace activist and writer Abu Sarah, speaking at the Limmud UK Jewish learning conference at Warwick University last month. “It doesn’t mean you agree.”

Photo: Aziz Abu Sarah, with camera around his neck

Abu Sarah was one of the few Palestinians in a sea of mostly British Jews, some 2,500 in total, who were spending five days in late December examining contemporary issues relating to the Jewish world.

Born the youngest of seven to Muslim parents in Bethany, a village east of Jerusalem on the slopes of the Mount of Olives, Abu Sarah remembers a small town where there wasn’t much to do. His father, who ran a produce import-export business with neighboring Arab countries, built the family a house surrounded by fruit trees and flowers.

“It was an empty place,” said Abu Sarah. “There were a bunch of families, no services whatsoever in the town, nothing to play with at all.”

He spoke no Hebrew and didn’t know any Jewish Israelis for the first 18 years of his life.

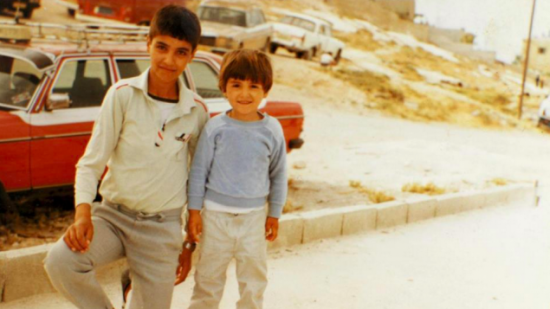

Abu Sarah began his presentation to Limmud with a sepia-toned photo of himself as a preschooler standing with his older brother, Tayseer. Tayseer was a second father to him, helping him negotiate schoolyard brawls and classroom dynamics. But when Abu Sarah was nine, his brother was imprisoned by the Israeli army for throwing rocks. He suffered injuries and died at the age of 19 after a year-long imprisonment.

Photo: Tayseer and Aziz Abu Sarah outside their childhood home in Bethany (Courtesy Aziz Abu Sarah)

There was no talk of reprisals or of acting out against the Israeli army. “My father didn’t allow us to talk about politics at all in our house, it was just forbidden,” said Abu Sarah.

But by that time, he was already out on the streets throwing rocks at Israeli cars.

“You don’t fully comprehend everything. It took years to figure out what the heck was going on,” he said in a conversation between sessions at Limmud. “When I started throwing stones, it was because we were bored, with nothing to do.”

In fact, his first stone was accidentally thrown at a neighbor’s car.

“I had seen it on TV, it was two weeks after the intifada started [in 1987] and we went out to the closest road and threw rocks at the cars,” he said. “It took us a while to figure out that you don’t throw rocks at your neighbors, but it was less out of anger and more out of boredom.”

Abu Sarah, a diligent student at his Islamic elementary school but one always on the lookout for loopholes, found out that one day of prayer at the Temple Mount was equal to 500 prayers. That brought him to pray once a month at the holy site.

Then in 1990, one of his neighbors, a close friend of Tayseer, was killed during riots at that very site, and Abu Sarah began to understand the broader context of the conflict he was playing a part in. By that time he was angry, bitter and well on his way to becoming active in Fatah, the official organization of the Palestinian Authority.

In high school, he became a Fatah organizer, writing and publishing content for the youth arm of the organization. He and his fellow leaders could gather thousands of students at a moment’s notice for a demonstration.

A former A student, Abu Sarah saw his grades suffer as a result of his political activity but he found it hard to care. He hid his activities from his parents, knowing they would fiercely disapprove.

“When I think about it now, the power we had at 16, 17, 18 — it’s scary,” he said.

Abu Sarah was in charge of writing political pamphlets for distribution, a task that he called “super dangerous” as it could earn him at least six months’ imprisonment. When his parents did eventually find out about his political work, his father made clear the possible consequences if he was caught by Israel’s armed forces.

“My dad said no violence and don’t trust anybody,” Abu Sarah recalled. “My father trusts nobody, he thinks somebody’s always listening in. People my dad’s age, they’re much more cautious. Someone could be shooting outside their house and they’ll say, ‘Everything’s fine.’”

When Abu Sarah graduated high school, he could have gone to work for Fatah in the Palestinian Authority, in a dead-end job he didn’t want.

Instead, he decided to learn Hebrew.

He enrolled in a Jerusalem ulpan, or Hebrew-language course, where there were more Jews than he’d ever encountered before. The experience was life-altering.

“The first week was bad, I felt so out of place,” he said. “But I had the most amazing teachers, and one was beyond incredible. She was such a leftist. She made statements that were shocking for me, like that Arafat is like Ben Gurion. She allowed things that I don’t think other teachers would have done.”

As a result of the ulpan, Abu Sarah ended up spending much of those early adulthood years forcing himself to look at other sides of the situation that had created his own reality. He visited Yad Vashem to learn about the Holocaust (“I thought they wouldn’t let me in”), and attended a Christian Bible college (“It was hard-core messianic”) in order to understand different perspectives on the Israeli and Palestinian conflict.

By the time the Second Intifada began in 2000, Abu Sarah had developed real friendships with Jews.

“At some point, the label thing didn’t appeal to me,” he said. “Some of my best friends were Jews, some are Christians, and I don’t care.”

In the course of starting his first tourism company, Abu Sarah met Rabbi Marc Gopin of George Mason University and began partnering with him on conflict resolution work. He’s now the executive director for George Mason University’s Center for World Religions, Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution.

Abu Sarah coordinates the group’s efforts in Islamic countries, including Afghanistan and Syria. He often works from his home in Virginia — he splits his time between Israel and the US — and says the project has offered him a completely new perspective on the entrenched situation in Israel.

“When you see other conflicts, you see that yours isn’t the worst,” he said. “That gave me hope.”

He, Gopin and another partner, Scott Cooper, also remade Abu Sarah’s existing tourism company into MEJDI Tours.

Photo: Aziz Abu Sarah delivers talks around the world (courtesy Aziz Abu Sarah)

Its aim is to create alternative encounters for tourists coming to Israel by offering Christian or Muslim groups the opportunity to meet Jews; they could join a Shabbat dinner, say, or meet the mayor of Efrat, a Jewish settlement in the West Bank. A Jewish group may end up visiting a Palestinian refugee camp or meeting a group of Arab artists.

The company also partners with National Geographic Expeditions, the only tour company to do so in Israel.

“It’s redefining tourism,” said Abu Sarah. “It’s not only about the sites, but using culture as a bridge, understanding another culture and letting it have an impact. If you don’t get that, there’s no point to travel.”

As the Limmud conference drew to a close, Abu Sarah was ready to head back to Israel, to his parents’ current home in Jerusalem. They moved there when Abu Sarah was 16 and trying to obtain an Israeli identity card, which wasn’t available to Palestinians living outside Jerusalem.

We finished our conversation in a hallway just before Abu Sarah was scheduled to deliver a lecture about Syria and the Islamic State terror group. He told me about his bout of thyroid cancer in 2010, when he was treated by Palestinian and Jewish doctors at Hadassah Hospital. That reminded him that people can stop looking at others’ identities when it’s irrelevant to the matter at hand.

“That is how it is for most people,” he said. “And that’s where we can overcome this enmity.”

This material is presented as the original analysis of analysts at S-CAR and is distributed without profit and for educational purposes. Attribution to the copyright holder is provided whenever available as is a link to the original source. Reproduction of copyrighted material is subject to the requirements of the copyright owner. Visit the original source of this material to determine restrictions before reproducing it. To request the alteration or removal of this material please email [email protected].

rosters

IMPORTANT LINKS

- Home

- Admissions

- Academics

- Research & Practice

- Center for Peacemaking Practice

- Center for the Study of Gender and Conflict

- Center for the Study of Narrative and Conflict Resolution

- Center for World Religions, Diplomacy, and Conflict Resolution

- Indonesia - U.S. Youth Leadership Program

- Dialogue and Difference

- Insight Conflict Resolution Program

- Parents of the Field Project

- Program on History, Memory, and Conflict

- Project on Contentious Politics

- Sudan Task Group

- Undergraduate Experiential Learning Project

- Zones of Peace Survey

- News & Events

- Student and Career Services

- Alumni

- Giving